Self-portraiture & split-screen : some coronavirus aesthetics

When artists “do” social distancing, they often of necessity become their own models or subjects. This resurgence of self-portraiture dovetails with the flourishing portrait-format (9:16 tall-screen) framing in video. A flourishing that led me to co-found the world’s first competition for vertical films in 2014. Usually simplistically ascribed to the development of handheld smartphones, I’d instead argue that vertical video reflects digital video’s freedom from physical standards; wrangling 1s and 0s is of a different order to exhibiting standardised film gauges. Tall-screen video promises a renaissance for the vertical orientation unprecedented since landscape-format paintings burst onto the scene in the early 1500s. And now it is helped along by its suitability for capturing ourselves as subjects, under confinement.

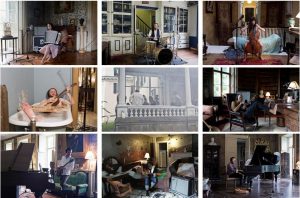

But what to do if your “covidement” means there’s only one of you, yet you need multiple actors? Enter split-screen. The newfound popularity of video group-chats (Zoom et al) since March 2020 has seen a plethora of mundane grid-like designs for such subdivided screens. The bordered split-screen is a form whose aesthetic heyday has perhaps been and gone with post-war Hollywood cinema: consider Pillow Talk‘s Doris Day and Rock Hudson on the phone from their provocatively split-screen bathtubs (1959) or The Thomas Crown Affair (right, 1968). Some more creative uses are to be found in online videos produced by newly isolated musicians. Sick of transcribing Bach suites for solo cello they instead looking for ways to visually multi-track themselves or collaborators. (A state of affairs perhaps presaged by Ragnar Kjartansson’s 9-channel masterpiece The Visitors (2012, left.))

But what to do if your “covidement” means there’s only one of you, yet you need multiple actors? Enter split-screen. The newfound popularity of video group-chats (Zoom et al) since March 2020 has seen a plethora of mundane grid-like designs for such subdivided screens. The bordered split-screen is a form whose aesthetic heyday has perhaps been and gone with post-war Hollywood cinema: consider Pillow Talk‘s Doris Day and Rock Hudson on the phone from their provocatively split-screen bathtubs (1959) or The Thomas Crown Affair (right, 1968). Some more creative uses are to be found in online videos produced by newly isolated musicians. Sick of transcribing Bach suites for solo cello they instead looking for ways to visually multi-track themselves or collaborators. (A state of affairs perhaps presaged by Ragnar Kjartansson’s 9-channel masterpiece The Visitors (2012, left.))

But there’s another kind of split-screen that avoids the black dividing lines brought to those films (from print layouts) by graphic designers such as Pablo Ferro. And that’s compositing or masking, which you see in my little video above: cutting around and combining aspects of a single scene either in-camera or in editing. The video is in fact one locked-off shot of about 10 minutes (first I ‘performed’ Id on the stairs, then to the Main Gallery for Ego, and finally ascended the Lantern Gallery for Superego). Divided into three in editing, then overlaid, each “layer” was judiciously cropped then colour-graded to make up for daylight fading as time wore on.

My PhD thesis (which was taking me from Svalbard to Greenland when borders closed, marooning me here, midway) proposes not these split-screens (which conventionally signify simultaneity) but multiple screens to bring together the vast spatiotemporal dimensions of climate change. The downside of such multiscreens are that they generally require a gallery space. (As I write I have just learnt that my video triptych anthropoScene IV : Adrift (∆Asea-ice), adjourned in March, will reopen at Galleri Svalbard from Monday, 18 May 2020‚ welcome news indeed!) Domestic screens facilitate split-screen presentation much more readily, though at the cost of an audience physically inhabiting multiscreen’s created worlds.

The very first “split screen” cinema from 1898 involved masking off parts of the image, either in-camera, or on-set. The two earliest such works that I could find are George Albert Smith’s Santa Claus and Georges Méliès’ The Four Troublesome Heads:

So, I confess: Id, Ego & Superego do social distancing is Méliès 101. His work can be seen as a progenitor of optical printing — which led to the digital compositing that’s recently become both ubiquitous and seamless in contemporary cinema. I think if I could be marooned in the lighthouse with only one other person my choice would be Georges Méliès.

We could get up to all sorts of creative mischief — especially with my digital camera and those four bothersome heads of his.

Adam Sébire

[…] 10, so if you missed seeing the adventures of Id, Ego & Superego in week 5 it’s to be found here. But I’m going to fill the rest of this post with some gratuitous lighthouse porn to try to […]