Prologue

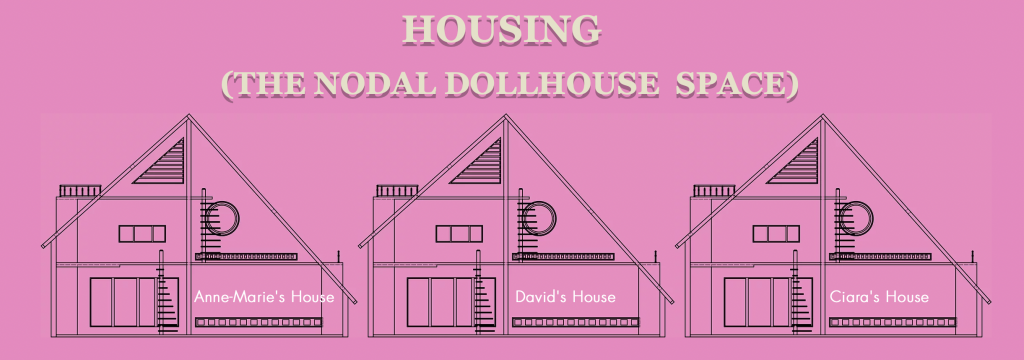

Art Arcadia and The Dollhouse Space, sharing common sympathies on residency program design and critical approaches to the architecture of ‘The Exhibition’, have long entertained the idea of somehow working together. Paola’s invitation to participate in this residency grew out of a conversation several years ago around a proposal I had written in response to a research project call: the idea of setting up DHS nodes in different geographical locations, thus creating a decentralised nodal network that is simultaneously large, but also operates at an autonomous, very small-scale, intimate level.

Established in 2018 and deliberately designed to handle physical dislocation (which, of course, has now become a baseline requirement in a Pandemic compromised, Brexit-broken Europe) The Dollhouse Space is a non-profit, experimental, bi-locational artspace with a tiny physical presence in The Netherlands and a virtual presence here: www.thedollhouse.space

My original proposal addressed a core problem of the International Project, namely, How do you combine big visions with the fact that, ultimately, people live in local environments? and my research project considers the dilemma described by EF Schumacher in “Small is Beautiful – A Study of Economics as if People Mattered.” (Blond & Briggs Ltd., 1973):

“In the affairs of men, there always appears to be a need for at least two things simultaneously, which, on the face of it, seem to be incompatible and to exclude one another. We always need both freedom and order. We need the freedom of lots and lots of small, autonomous units, and, at the same time, the orderliness of large-scale, possibly global, unity and co-ordination. When it comes to action, we obviously need small units, because action is a highly personal affair and one cannot be in touch with more than a very limited number of persons at any one time. But when it comes to the world of ideas, to principles or ethics, the indivisibility of peace and also of ecology, we need to recognise the unity of mankind and base our actions upon this recognition.”

to ask: “How do we rebalance?”

The DHS design addresses this on two levels:

Firstly, it simultaneously co-exists as a (theoretically) infinitely expandable virtual space and a tiny physical space. Doing so it inhabits the problem Schumacher highlights in relation to size: ‘to hold two seemingly opposite necessities of truth in mind at the same time’, providing a dual-scale, trans-reality structure that offers the opportunity to explore the tensions between the small and the large, the physical and the virtual space, between real and fictive spaces, all the while treading lightly on our planet’s vulnerable surface.

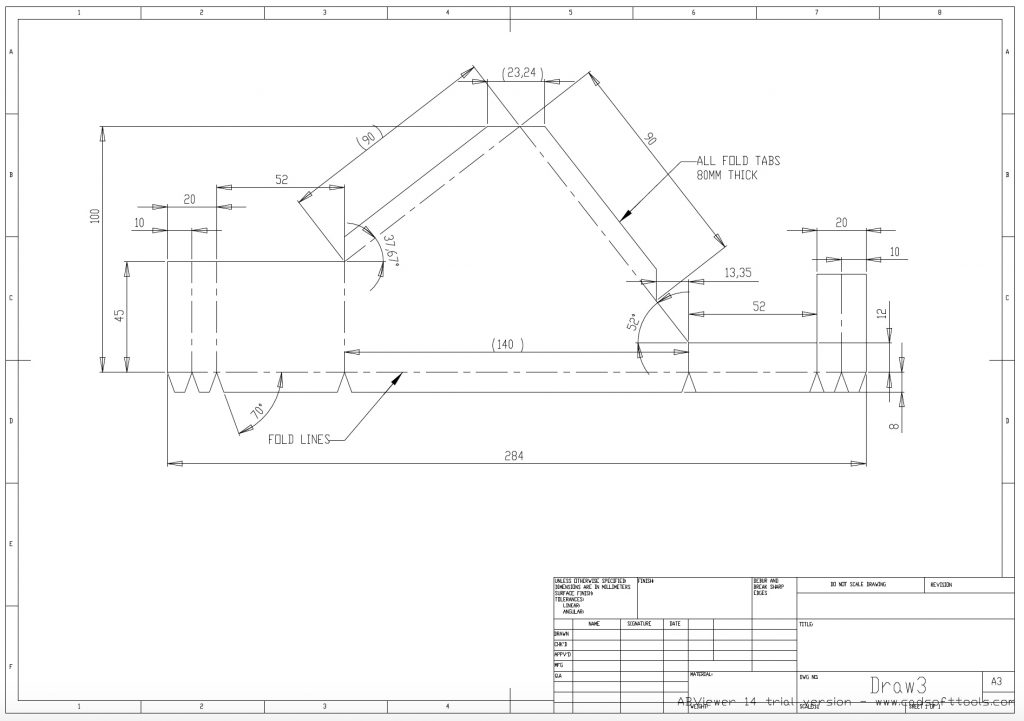

Plans for The Paper Dollhouse (Public Event, The DollHAUS, 2020) CAD drawing by Sean Finnegan.

Plans for The Paper Dollhouse (Public Event, The DollHAUS, 2020) CAD drawing by Sean Finnegan.

Flat Pack: Paper Dollhouse + Dollhaus exhibition installation kit AssemblyVideo

Secondly, it is enormously capable of nodal growth.

The DHS founding physical model is a second-hand Dutch dollhouse, mass produced by the toy manufacturer, Okkerse (OKWA) in the 1970s. The DHS model refers back critically to the precursor of the modern European museum – the Wunderkabinett – the elite practice of acquiring and displaying a collection, carrying aspects of this historic practice forth along a different trajectory. An instance of a unit among many it lacks the precious tag of individualism attached to custom made, artisanal dollhouses, such as Sara’s Dollhouse (Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem), the Doll’s House of Petronella Oorman (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam) or the more contemporary Miss Lucy’s Dollhouse (NYC) that hold places in the Western art-historical canon. In the case of the DHS, the mass-produced container becomes bespoke through the activity of its occupants.

The Dollhouse Space OKWA, 1974. Photo by Ciara Finnegan 2018.

The OKWA dollhouses are physically small enough to be inexpensively shipped worldwide.* Inherent in their export nest questions about colonial architecture, adaptability, local customisation, inviting an examination of minor architectural histories across different countries – not the architectural histories of the Grand Palais, The Museum or The University – but architectural and social histories of common housing.

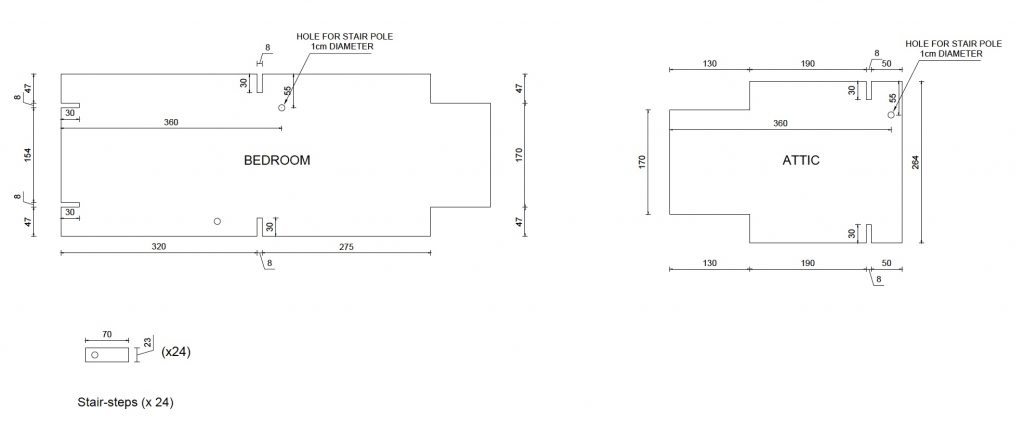

*Furthermore, having retrospectively drawn up the architectural plans for the OKWA dollhouse, it is now even more shippable as either the plans themselves, to be cut out on location, or as a pre-cut, easy-to-assemble flat-pack.

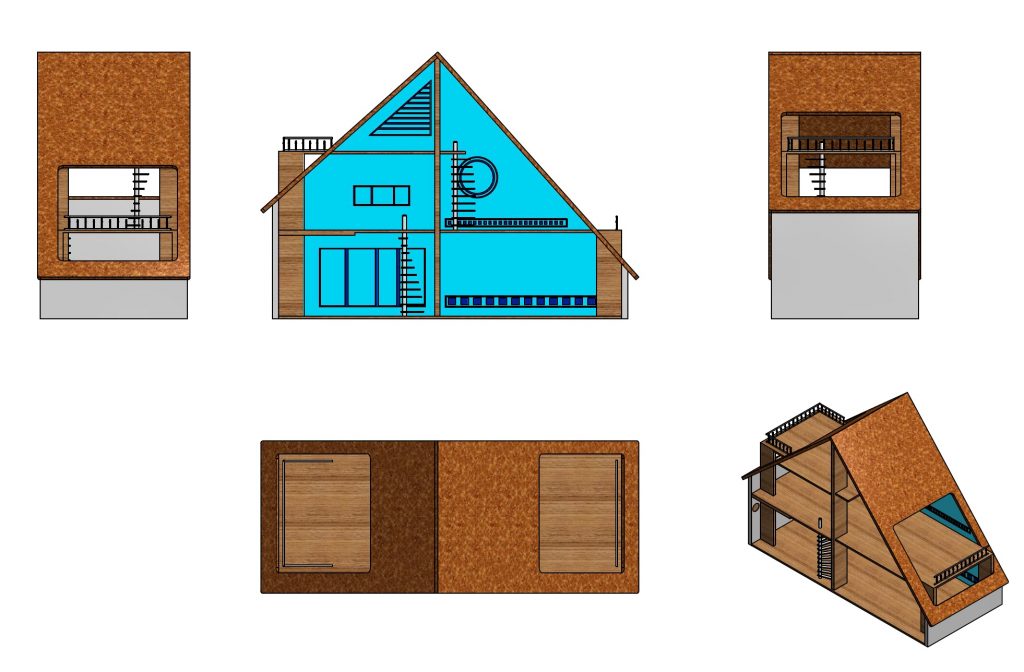

3D mock-up, The Dollhouse Space 2018. CAD drawings by Sean Finnegan.

3D mock-up, The Dollhouse Space 2018. CAD drawings by Sean Finnegan.

In practical terms, as a research vehicle, the DHS presents as a simple design that is very easy to set-up and run. It is a model that can scale horizontally with very low set-up and running costs and is easy to implement in both remote, rural communities and densely populated, high-rental inner cities.

The template upon which I have built the virtual Dollhouse Space is also easily reproducible and cost-efficient. The online software I use to build the virtual rooms, inexpensive, user-friendly and easily accessible.

The Dollhouse Space architectural plans. Illustrator Drawings by Ciara Finnegan. 2020.

The Dollhouse Space, in both its virtual and physical manifestations, functions as both exhibition site and studio laboratory/process rooms: sometimes this distinction is clearly indicated, sometimes it is deliberately obscured, sometimes it is marked only by inflection. The online rooms are not a virtual model of their equivalent in the physical Dollhouse, although they are intimately connected, existing as both separate and not separate spaces. The magic arises in the play between realities; in the slippages between physical and virtual, between real and fictive spaces.

The DHS is always in (at least) two places at once. As a nodal network, it imagines a dynamic shimmering canvas, coloured by the local practices and cultural habits of the individual nodes. With nodes in different physical locations, the DHS, like a distributed computing model, has the collective potential to substantially increase the focus on ecologically intelligent art production and substantially decrease art’s carbon footprint. As a thoroughly networked, de-centralised system, this model also has the potential to embody the radical change necessary to address the inequalities and biases endemic in existing, out-moded, massive institutional structures. It shifts in time and space, it opens up other realities and, against a backdrop of huge, immersive, multi-sensorial installation artworks, by virtue of its physical tininess and the otherness of the virtual, reinstates the power of the imagination.

And now I get to play in one of these nodes, Housing with and alongside Anne-Marie and David in their houses!

Ciara Finnegan