Going with the floes

It’s hard to overstate the importance of sea ice for life at Earth’s poles. As water transmutes from liquid to solid it transforms the existence of lifeforms, communities and ecosystems surrounding it; particularly for those who’ve adapted to living either atop or below it.

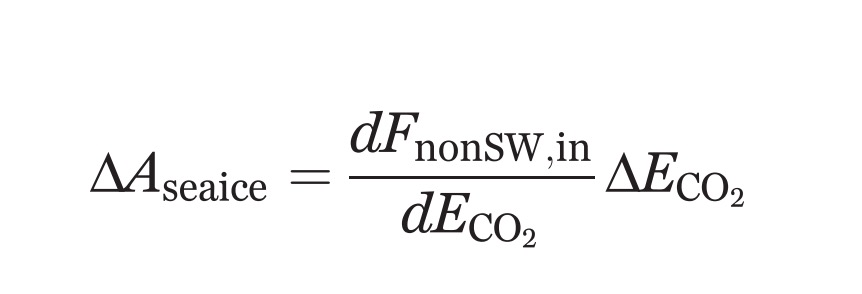

As an Australian who’d never set foot on sea ice my interest in it was kindled, oddly enough, by a mathematical formula published in the peer-reviewed journal Science in 2016:

The research behind the equation discovered sea ice decline was in direct relationship to the increase manmade greenhouse gas emissions: every additional tonne of CO₂ we pumped into the atmosphere equated to 3m² of Arctic sea ice that would not regenerate next winter. Here at last, I thought, was a breakthrough for my PhD exploring visual representation of the difficult-to-perceive “hyperobject” of climate change. In the fate of sea ice lay the ability to mathematically correlate cause and effect; to attribute the impact of carbon-intensive societies upon our environment. Exploring the ramifications of this took me to Greenland in May 2018: a journey emitting 5.23t of CO₂e and melting 15.69m² of sea ice, which formed the basis of my multi-screen artwork AnthropoScene IV: Adrift (?Asea-ice) .

Witnessing the dramatic melt and break-up of sea ice back then made me wonder: what stories could also be told of its formation? And how much longer would we be able to tell these stories with the Arctic now predicted to be free of sea ice in summers before 2050? Visually this transformation of sea into ice promised to be equally extraordinary yet I couldn’t find a lot of documentation, let alone art exploring this — with the exception of photographs and paintings of unfortunate explorers’ ships crushed by pack ice (notably Frank Hurley’s extraordinary photos of Ernest Shackleton’s ship destroyed in Antarctica in 1915, and rediscovered yesterday, 9 March 2022).

The tired trope of resourceful man versus unrelenting ice is exemplified in the title and content of this month’s Netflix blockbuster, Against the Ice (set in Greenland but mostly shot in Iceland … for reasons of practicality that soon became apparent to me!) I didn’t want to shoot in Iceland though; only in an Inuit society could I understand how sea ice had become fundamental to a way of life. Contemplating several locations to tell this story I settled upon Uummannaq — despite the seemingly insurmountable spelling difficulties it posed, even to someone who once lived in Woolloomooloo — after finding an image that looked like the island was exploding through of a pane of cracked of glass: fresh sea ice.

The tired trope of resourceful man versus unrelenting ice is exemplified in the title and content of this month’s Netflix blockbuster, Against the Ice (set in Greenland but mostly shot in Iceland … for reasons of practicality that soon became apparent to me!) I didn’t want to shoot in Iceland though; only in an Inuit society could I understand how sea ice had become fundamental to a way of life. Contemplating several locations to tell this story I settled upon Uummannaq — despite the seemingly insurmountable spelling difficulties it posed, even to someone who once lived in Woolloomooloo — after finding an image that looked like the island was exploding through of a pane of cracked of glass: fresh sea ice.

(Hearing that they ran an outpost of El Sistema on the island sealed the deal: a revolutionary Venezuelan program for transforming the lives of disadvantaged youth through music, 32 Inuit children were enrolled in it at Uummannaq Polar Institute and periodically even played concerts on the sea ice. But that’s another story…)

With the location chosen, the only other question was when to arrive, to capture Uummannaq fjord’s miraculous moment of transformation from liquid to solid? Most of last century, the answer would have been well before Christmas. A long-time resident of Uummannaq recalled how last century, students from the fjord’s surrounding settlements who were boarding on Uummannaq would return home each Christmas by dog sledge.

But in the same breath she mentioned that sea ice had now become so unreliable in December that this had been neither safe nor possible for some decades, and that last year there had barely been 6 weeks of human activity on the unstable sea ice all winter. On this evidence it seemed a bad time to be beginning a career as a Greenlandic sledge dog.

Optimistically, and figuring that the absence of sea ice would in any case be half the story, I chose the end of December to stay almost 2 months. I could only afford accommodation in the off-season, and come March dog sledging tourists and expeditioners would appear, eager to visit post-pandemic. It would be cold and dark, and filming conditions would be miserable, but I had to be there then.

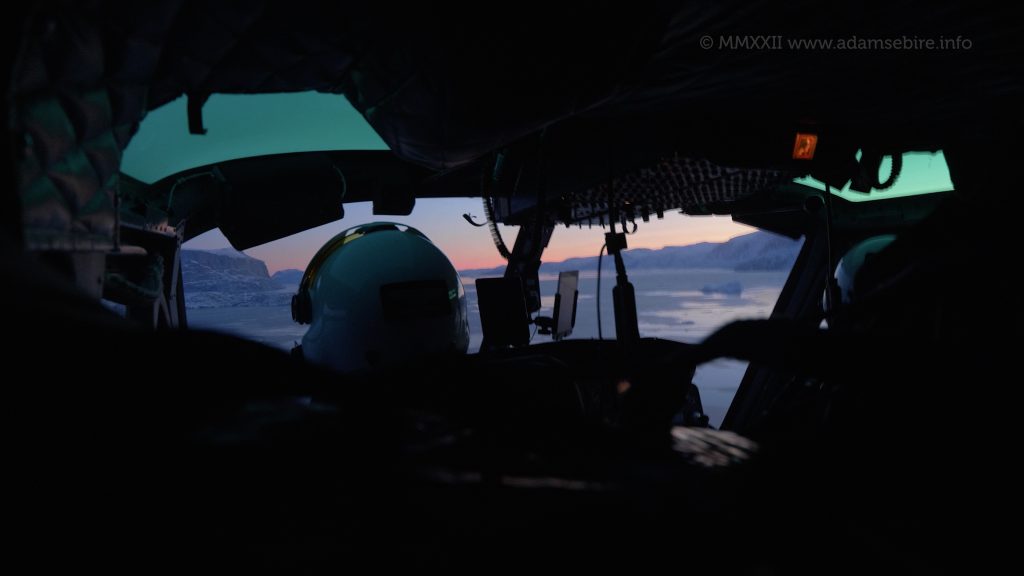

You can thus imagine my mixed emotions on the 12 minute helicopter journey across the fjord, crammed in behind a crate of iceberg lettuces (Class 1º) from Spain, as I looked out upon kilometre after stunning kilometre of nascent sea ice crystals formed atop the calm sea surface. But, darn it, like the absent father-to-be stuck in traffic — it seemed I had already missed the moment of their birth!

You can thus imagine my mixed emotions on the 12 minute helicopter journey across the fjord, crammed in behind a crate of iceberg lettuces (Class 1º) from Spain, as I looked out upon kilometre after stunning kilometre of nascent sea ice crystals formed atop the calm sea surface. But, darn it, like the absent father-to-be stuck in traffic — it seemed I had already missed the moment of their birth!

On arrival I wandered around in the 2 hours of civil twilight, in disbelief both at the scene, but also the knowledge that I was here at all. Dazed, I took shots of boats atop the frozen harbour until my batteries died under the crepuscular light. These boats would not budge until Spring; I was certain of it. The sea, already -1.8ºC would get colder and the ice, thicker and ever more stable as winter set in, I told myself.

I could not have been more mistaken…